Liver Cancer

Liver Cancer: A Comprehensive Guide to a Silent but Surging Disease

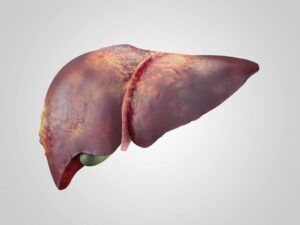

Introduction: The Multifaceted Assault on the Liver

Liver cancer, specifically hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), represents a growing and formidable global health challenge. It is the sixth most common cancer worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths, with its incidence rising steadily in many Western countries over the past four decades. Unlike many cancers, HCC almost exclusively arises in a liver already damaged by chronic disease, making it a “second-hit” malignancy where cirrhosis is the single most important risk factor. The liver’s remarkable regenerative capacity becomes its tragic flaw in this context, as chronic injury and repair cycles create a fertile ground for genetic errors and malignant transformation. This guide provides a detailed exploration of HCC’s complex etiology, silent progression, modern diagnostic algorithms, and the rapidly evolving therapeutic landscape that offers hope even for advanced disease.

Part 1: Understanding the Liver and Types of Liver Cancer

The liver is the body’s metabolic powerhouse, responsible for detoxification, protein synthesis, bile production, and glucose regulation. Most primary liver cancers (starting in the liver) are:

Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC): Accounts for 75-85% of cases. Arises from the main liver cells (hepatocytes).

Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma (ICC): Accounts for 10-15%. Arises from the bile ducts within the liver. Often grouped with HCC but is a distinct disease with different risk factors and treatment.

Rare Types: Hepatoblastoma (in children), angiosarcoma.

Metastatic cancer (from colon, breast, lung, etc.) in the liver is 30 times more common than primary liver cancer but is not classified as “liver cancer.”

Part 2: The Pathogenesis: Cirrhosis as the Precancerous Bed

Over 80-90% of HCC cases develop in the setting of cirrhosis. Cirrhosis is the end-stage of chronic liver injury, where healthy liver tissue is replaced by scar tissue (fibrosis) and regenerative nodules.

The Vicious Cycle: Chronic injury (e.g., from virus, alcohol, fat) → inflammation and hepatocyte death → activation of hepatic stellate cells → deposition of collagen (fibrosis) → distorted liver architecture and regeneration → cirrhotic nodules.

Dysplastic Nodules: Within cirrhotic livers, some nodules acquire genetic mutations and become precancerous (low-grade then high-grade dysplastic nodules).

The Final Step: Additional driver mutations (e.g., in TERT, TP53, CTNNB1) propel a dysplastic nodule into invasive HCC.

Non-Cirrhotic HCC: Occurs in settings like chronic Hepatitis B (where HCC can develop before cirrhosis), aflatoxin exposure, and metabolic dysfunction.

Part 3: Etiology and Risk Factors – A Global Mosaic

The leading causes of liver disease, and thus HCC, vary geographically but converge on cirrhosis.

Major Global Causes:

Chronic Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Infection: The leading cause worldwide, especially in Asia and Africa. HBV DNA integrates into the host genome, driving cancer even without full cirrhosis.

Chronic Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Infection: A leading cause in the U.S., Europe, and Japan. Cure of HCV with antivirals reduces but does not eliminate HCC risk if cirrhosis is already established.

Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease (ALD): Chronic, heavy alcohol use is a major contributor in Western countries.

Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) / Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis (MASH): Formerly known as NAFLD/NASH. This is the fastest-growing cause of HCC in the West, driven by the epidemics of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. MASH can lead to cirrhosis and HCC.

Other Significant Risk Factors:

Aflatoxin Exposure: A potent carcinogen produced by fungi on poorly stored grains and nuts; synergizes with HBV in parts of Africa and Asia.

Tobacco Smoking.

Type 2 Diabetes and Obesity.

Genetic Hemochromatosis (iron overload).

Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency.

Part 4: Clinical Presentation – The Challenge of Late Symptoms

Early HCC is asymptomatic. Symptoms typically emerge with significant tumor burden or liver decompensation, leading to late-stage diagnosis.

Early/Incidental: Often found during surveillance ultrasound in a patient with known cirrhosis.

Advanced Symptoms:

Right Upper Quadrant Abdominal Pain or dull ache.

Unexplained Weight Loss and Loss of Appetite.

Early Satiety (feeling full quickly) from an enlarged liver.

Nausea, Vomiting, Fatigue.

Signs of Liver Decompensation: New or worsening jaundice (yellow skin/eyes), ascites (abdominal swelling), hepatic encephalopathy (confusion), variceal bleeding.

Paraneoplastic Syndromes: Rarely, HCC can produce hormones causing symptoms like hypercalcemia or erythrocytosis.

Part 5: Diagnosis and Staging – The Non-Biopsy Era for HCC

HCC has a unique diagnostic pathway. In patients with cirrhosis, imaging characteristics are often so specific that a biopsy is not required for diagnosis, avoiding the risk of tumor seeding.

Surveillance (For At-Risk Patients):

Who: All patients with cirrhosis (any cause) and certain high-risk Hepatitis B patients without cirrhosis.

How: Abdominal Ultrasound with or without Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) blood test every 6 months.

Diagnostic Imaging (“LI-RADS” Criteria):

When a surveillance ultrasound finds a nodule >1 cm, a multiphase CT or MRI of the liver is performed. HCC has a classic vascular pattern:

Arterial Phase Hyperenhancement (APHE): The tumor “lights up” brightly as it is fed by new, abnormal arteries.

Washout: In the delayed/portal venous phase, the tumor becomes darker than the surrounding liver as the contrast agent “washes out.”

Capsule Enhancement: A rim of enhancement may be seen.

A lesion with these specific features in a cirrhotic liver is diagnosed as HCC without a biopsy.

Tumor Markers:

Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP): Elevated in ~60-70% of HCCs. Very high levels (>400 ng/mL) are diagnostic. Used for monitoring response to treatment.

AFP-L3, DCP (PIVKA-II): Emerging complementary markers.

Staging Systems:

Unlike most cancers, staging must incorporate both tumor extent and underlying liver function.

The Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) Staging System: The global gold standard. Integrates:

Tumor Stage: Number, size, vascular invasion.

Liver Function: Measured by Child-Pugh class (based on bilirubin, albumin, INR, ascites, encephalopathy).

Performance Status: Patient’s overall health and functional capacity.

The BCLC stage directly dictates the recommended treatment pathway.

Part 6: The Treatment Paradigm – A Stage-Directed Approach

Treatment is complex and requires a multidisciplinary team (hepatologist, hepatobiliary surgeon, interventional radiologist, oncologist).

Curative-Intent Treatments (For Early-Stage Disease – BCLC 0/A):

Liver Transplantation: The optimal treatment for eligible patients. Removes both the tumor and the diseased, precancerous liver. Strict criteria (e.g., Milan Criteria: single tumor ≤5 cm, or up to 3 tumors all ≤3 cm, no vascular invasion) must be met.

Surgical Resection: Removal of the tumor-bearing part of the liver. Only possible if the tumor is resectable and the remaining liver function is adequate (often requires non-cirrhotic liver or very well-compensated cirrhosis).

Local Ablation: For small tumors (<3 cm) not suitable for surgery/transplant.

Radiofrequency Ablation (RFA) / Microwave Ablation (MWA): A needle destroys the tumor with heat.

Percutaneous Ethanol Injection.

Bridge/Downstage Therapies (For Patients Awaiting Transplant or to Shrink Tumors):

Transarterial Chemoembolization (TACE): The most common procedure for intermediate-stage disease. Chemotherapy is delivered directly into the tumor’s blood supply, followed by blocking the artery.

Transarterial Radioembolization (TARE / Y-90): Delivers microscopic radioactive beads directly to the tumor.

Stereotactic Body Radiotherapy (SBRT): High-precision external radiation.

Systemic Therapy (For Advanced-Stage Disease – BCLC C):

This field has been revolutionized in the last 5-7 years.

First-Line Therapies:

Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab (“Atezo/Bev”): An immunotherapy (PD-L1 inhibitor) + an anti-angiogenic drug. This is the current global standard first-line treatment, showing superior survival over the previous standard.

Tremelimumab + Durvalumab: A dual immunotherapy combination (CTLA-4 + PD-L1 inhibitors).

Second-Line & Other Options:

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs): Sorafenib (the original breakthrough), Lenvatinib, Cabozantinib, Regorafenib.

Ramucirumab: For patients with high AFP.

Pembrolizumab: Immunotherapy as a later option.

Supportive/Palliative Care (For End-Stage Disease – BCLC D):

Focuses on managing symptoms (pain, ascites) and maintaining quality of life.

Part 7: Prevention and the Future

Primary Prevention: Vaccination against Hepatitis B, treatment of Hepatitis C, reduction of alcohol use, and public health strategies to combat obesity and diabetes (to prevent MASLD).

Secondary Prevention: Rigorous surveillance in at-risk populations (cirrhosis) to detect HCC at its earliest, most treatable stage.

Tertiary Prevention: Adjuvant therapies after curative treatment to prevent recurrence (an area of active research).

Conclusion: A Battle on Two Fronts

Liver cancer is a disease of duality: a battle against both the malignant tumor and the underlying dysfunctional liver. Its rising tide, fueled by metabolic disease, demands urgent public health attention. For the individual patient, however, the outlook is brighter than ever. The convergence of effective surveillance, sophisticated non-invasive diagnosis, a robust stage-directed treatment algorithm, and breakthrough systemic immunotherapies has transformed a once rapidly fatal diagnosis into a manageable condition for many. Success hinges on early detection through regular monitoring of at-risk individuals and access to a specialized multidisciplinary care team capable of navigating the complex interplay between tumor biology and liver reserve.

Key Takeaways:

Cirrhosis is the primary driver of HCC. Managing underlying liver disease is foundational.

Early detection through 6-month ultrasound surveillance in cirrhotic patients is life-saving.

Treatment is highly specialized and stage-dependent, ranging from transplant to ablation to novel drug combinations.

Systemic therapy has entered an immunotherapy era, significantly improving survival for advanced disease.

Resources:

The Liver Cancer Center (Johns Hopkins): Patient resources.

American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD): Practice guidelines.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of a hepatologist or oncologist specializing in liver cancer.