Thyroid Cancer

Thyroid Cancer: A Comprehensive Guide to the Increasingly Common, Yet Highly Treatable, Cancer

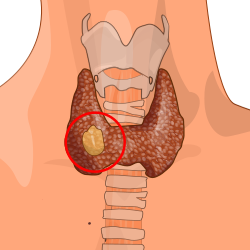

Introduction: The Modern Epidemic of Detection

Thyroid cancer presents a unique paradox in oncology: its incidence has more than tripled over the past four decades, making it one of the fastest-rising cancers, yet mortality rates have remained stable and remarkably low. This “epidemic” is almost entirely due to the overdiagnosis of small, indolent papillary microcarcinomas—tumors that would likely never cause harm—uncovered by advanced imaging (CT, MRI, ultrasound) for unrelated issues. The thyroid, a butterfly-shaped gland at the base of the neck, is central to metabolism, and cancers arising from it are predominantly slow-growing and highly curable. However, a small subset behaves aggressively. The central challenge in modern thyroid cancer care is not simply achieving cure, but stratifying risk to avoid overtreating harmless cancers while aggressively managing the dangerous few. This guide details the biology, diagnosis, risk-adapted management, and evolving debates in thyroid cancer.

Part 1: Anatomy, Function, and Types of Thyroid Cancer

The thyroid gland produces hormones (T3 and T4) that regulate heart rate, blood pressure, body temperature, and weight. Cancers arise from two main cell types:

1. Differentiated Thyroid Cancers (DTCs) – 95% of Cases

These arise from follicular cells, which produce hormone. They generally retain some ability to take up iodine and produce thyroglobulin, features used in treatment and monitoring.

Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma (PTC): 80-85% of all cases. Characterized by slow growth, excellent prognosis, and classic features like psammoma bodies and nuclear grooves. Includes the follicular variant of PTC (FVPTC), which has a similar excellent prognosis.

Follicular Thyroid Carcinoma (FTC): 10-15% of cases. Diagnosed by the presence of capsular or vascular invasion. Prognosis is slightly less favorable than PTC but still very good. Hurthle cell carcinoma is a variant of FTC.

2. Medullary Thyroid Carcinoma (MTC) – 4%

Arises from parafollicular C-cells, which produce calcitonin. 25% are hereditary, associated with Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 2 (MEN2) syndromes. More aggressive than DTCs and does not take up iodine.

3. Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma (ATC) – <2%

One of the most aggressive human cancers. Arises from dedifferentiation of existing DTC. Rapidly growing, almost uniformly fatal, but extremely rare.

Part 2: Risk Factors and the Role of Radiation

Gender: Women are 3 times more likely to be diagnosed than men (likely due to hormonal influences and higher rates of medical imaging).

Age: Peak incidence is in the 40s and 50s.

Radiation Exposure: A well-established risk factor, particularly childhood exposure to medical radiation (for acne, tonsillitis) or environmental radiation (nuclear fallout). Modern medical imaging uses much lower doses.

Family History: Most thyroid cancers are sporadic, but having a first-degree relative with thyroid cancer increases risk. Specific syndromes include:

MEN2 (for MTC).

Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP).

Cowden Syndrome.

Iodine Deficiency: Associated with an increased risk of follicular and anaplastic cancers.

Part 3: Signs, Symptoms, and the Incidental Nodule

Most thyroid cancers present as asymptomatic nodules discovered incidentally.

Primary Symptom: A palpable lump or nodule in the front of the neck. However, over 95% of thyroid nodules are benign.

Other Symptoms (Less Common, May Suggest Advanced Disease):

Hoarseness or voice changes (recurrent laryngeal nerve involvement).

Difficulty swallowing or breathing (compression of esophagus/trachea).

Swollen lymph nodes in the neck.

Persistent cough not due to a cold.

The Incidentaloma Era: Vast majority of nodules today are found on imaging for other reasons (carotid ultrasound, CT of chest for trauma). This has driven the overdiagnosis epidemic.

Part 4: Diagnosis and Risk Stratification – The FNA Biopsy and Beyond

Diagnosis follows a clear, stepwise pathway focused on identifying the small percentage of nodules that are cancerous.

Clinical Exam and Neck Ultrasound: Ultrasound is the key initial test. It evaluates the nodule’s size, composition (solid vs. cystic), echogenicity, margins, and the presence of microcalcifications. It also examines the cervical lymph nodes.

The TIRADS Score (Thyroid Imaging Reporting and Data System): A standardized system (like BI-RADS for breast) that categorizes nodules from TR1 (benign) to TR5 (highly suspicious) based on ultrasound features. Guides the need for biopsy.

Fine-Needle Aspiration (FNA) Biopsy: The definitive diagnostic procedure. A thin needle extracts cells from the nodule for cytological analysis. Results are classified by The Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology (Categories I-VI), ranging from non-diagnostic to malignant.

Molecular Testing (On FNA Samples): A revolutionary tool used for nodules with indeterminate cytology (Bethesda III/IV). Tests like ThyroSeq or Afirma GSC analyze the nodule’s genetic profile to rule in or rule out cancer, preventing unnecessary surgery for benign nodules.

Additional Tests: For MTC, serum calcitonin and CEA are diagnostic tumor markers. Genetic testing for RET proto-oncogene mutations is critical for patients and families.

Part 5: The Modern, Risk-Adapted Treatment Paradigm

Treatment is no longer “one-size-fits-all.” It is tailored based on histology, tumor size, presence of metastases, and, for DTC, a dynamic risk recurrence stratification.

A. Surgery: The Primary Treatment for Nearly All Cancers

Lobectomy: Removal of one thyroid lobe. Now standard for low-risk, small (≤4 cm) cancers confined to one lobe with no aggressive features or lymph node spread.

Total Thyroidectomy: Removal of the entire gland. Indicated for: tumors >4 cm, bilateral disease, presence of extrathyroidal extension, lymph node metastases, aggressive histology (e.g., tall cell variant), or if radioactive iodine therapy is planned.

Central Neck Dissection: Removal of lymph nodes in the central compartment of the neck. Performed if lymph node involvement is suspected or confirmed.

B. Radioactive Iodine (RAI) Ablation/ Therapy (For DTC Only):

Principle: Thyroid cells (and DTC cells) take up iodine. Radioactive iodine (I-131) is administered orally; it destroys residual thyroid tissue and cancer cells.

Modern Use: Not routine for low-risk cancers. Used selectively for intermediate and high-risk patients to treat known disease or reduce recurrence risk. Its use has declined significantly due to evidence of overtreatment.

C. Thyroid Hormone Suppression Therapy:

All patients who undergo total thyroidectomy require lifelong thyroid hormone (levothyroxine) replacement. For higher-risk patients, the dose is set slightly higher to suppress TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone), which can stimulate any remaining cancer cells.

D. Treatment for Advanced/Progressive Disease:

For DTC and MTC that no longer responds to surgery/RAI.

Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs): Sorafenib and Lenvatinib for progressive, RAI-refractory DTC. Cabozantinib and Vandetanib for MTC.

RET Inhibitors: Selpercatinib and Pralsetinib are highly effective for MTC and DTC with RET mutations/fusions.

NTRK Inhibitors: For tumors with rare NTRK gene fusions.

External Beam Radiation: For local control of unresectable disease in the neck or bone metastases.

Clinical Trials: For ATC, which may respond to combination immunotherapy/kinase inhibitors.

Part 6: Prognosis, Follow-Up, and The Challenge of Overdiagnosis

Prognosis: Exceptional for DTC. The 5-year relative survival rate for localized papillary cancer is >99%. Even with regional spread, it is 98%. Survival drops for distant metastases but is improving with new therapies. MTC and ATC have poorer prognoses.

Follow-Up: Based on dynamic risk stratification. Uses:

Serial Neck Ultrasounds.

Stimulated or Unstimulated Thyroglobulin Levels (a tumor marker for DTC).

For MTC: Calcitonin and CEA levels.

The Overdiagnosis/Overtreatment Crisis: An estimated 50-90% of thyroid cancers currently diagnosed in developed countries may never cause symptoms or death. This has led to a major paradigm shift: for very low-risk papillary microcarcinomas (<1 cm), active surveillance (monitoring with ultrasound, no immediate surgery) is now a recommended option in expert centers, avoiding surgery and its lifelong consequences for a disease that may never progress.

Conclusion: Precision in an Era of Plenty

Thyroid cancer care has evolved from reflexive, maximal treatment to a nuanced, risk-adapted model. The goals are now twofold: to cure lethal disease with aggressive, multimodal therapy, and to protect patients with indolent disease from the harms of unnecessary intervention. This requires sophisticated diagnostics (molecular testing), personalized surgical planning, selective use of RAI, and, for select patients, the courage to monitor rather than operate. For the vast majority of patients, a thyroid cancer diagnosis, while frightening, carries an excellent prognosis for a normal, healthy life. The future lies in better molecular tools to distinguish the dangerous tiger from the harmless kitten at the time of diagnosis.

Key Takeaways for Patients:

Most thyroid nodules are benign. Most thyroid cancers are highly curable.

Ask about the size and risk features of your cancer. A low-risk microcarcinoma may only need observation.

Molecular testing on FNA biopsy can prevent unnecessary surgery.

For low-risk cancer, a lobectomy may be sufficient, preserving half your thyroid function.

Long-term follow-up is essential but can be minimal for truly low-risk disease.

Resources:

American Thyroid Association (ATA): www.thyroid.org (Patient guidelines)

American Cancer Society: Detailed guide on thyroid cancer.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of an endocrinologist or endocrine surgeon specializing in thyroid cancer.